The problem with the site-to-site VPN is perhaps it is too easy. It’s cost effective, easy to configure … but not always the right answer. And sometimes a site-to-site VPN is the right answer, but how it’s been set up may not be the best way.

Here are some tips on deciding if you need a site-to-site VPN and some considerations about how to configure it for the best performance.

When Simplicity Becomes Complexity

Many times, a company’s wide area network goes from two or three site-to-site VPNs to many more as they grow. However, if growth is not taken into consideration when the VPN architecture is built, it can become unwieldy. This is especially true in environments where every site needs to communicate.

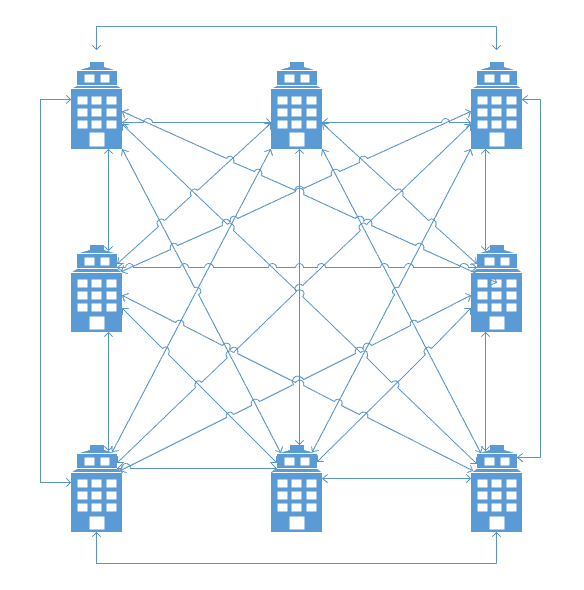

In a full mesh design, as you add sites, the number of site-to-site connections to manage grows exponentially. At a certain point, usually around five or six sites, this becomes impractical to maintain, as you can see below in this diagram (which is also accounting for redundancy … which you should also be doing.)

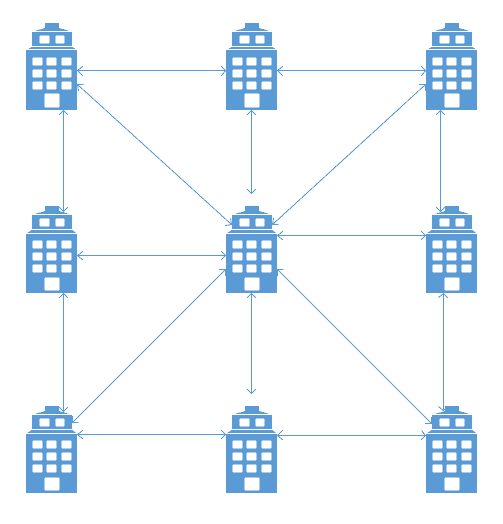

Once you see that you are going to add sites at that rate, you should make plans to switch to a hub and spoke design. This is easier said than done depending on your firewall/VPN concentrator solution. As you can see from the below diagram, it’s much less complex than continuing to do a full mesh design.

How VPNs Are Done Differently

A lot products like the Cisco ASA and SonicWall devices rely on policy-based VPNs. This VPN configuration routes all traffic to the internet interface and relies on a myriad of policies to make sure interesting traffic is sent to the proper VPN tunnel.

A much simpler and robust method is to set up VPN virtual interfaces. This is the go-to method for Fortinet, Brocade Vyatta and non-ASA Cisco routers. In this configuration, each VPN tunnel is treated as an interface on the device. From there are can apply any service or feature as you would a physical interface connected to a network. You can perform dynamic routing via OSPF over your VPN connections.

Site-to-Site VPN vs Leased Circuit

The primary issue with site-to-site VPNs is that you need to know when to use them and when to use a leased circuit.

As environments grow, they can see a decrease in application performance over the VPN connection, since they all rely on the internet. Chief among these is VoIP applications, since you cannot QoS the Internet. Once you begin to grow to the extent that voice quality is an issue, you should focus on going to a leased circuit.

In fact, if the traffic going between your sites is important enough that you cannot afford any outages, you should use a leased circuit, or even a point-to-point wireless bridge (depending on the conditions). Yes, leased circuits will cost more because they are a dedicated resource with more strict SLAs, but you’re paying for reliability.

Site-to-site VPNs are best for smaller offices without a lot of traffic, or as backup/failover connections to come into play if the primary connection fails.

Common VPN use cases:

- Backup connection

- Small office without a lot of traffic

- Environments without a need for applications that are sensitive to latency, jitter and drops, i.e. voice, video conferencing

- Environments without a need for top notch reliability or speed.

Common leased circuit use case:

- Large environments

- Cannot afford an outage

- Sensitive applications like voice, video, etc.

Using a Site-to-Site VPN as Your Backup Connection

Of course, site-to-site VPNs make an excellent backup connection between sites. Combining a leased circuit with a VPN as its backup allows you to get good performance and some level of redundancy while keeping costs lower.

When it comes to setting up your VPN, be sure to provide the highest level of security by choosing better encryption. Additionally, enable Perfect Forward Secrecy and do not use Aggressive Mode.

Fully Configuring Your Site-to-Site VPN Properly

Finally, you’re free to control the traffic that is allowed over the VPN. Many folks overlook this part and don’t limit the VPN to just the necessaries, which can also degrade your performance overall. Pay attention to what purposes your VPN is going to serve and tailor your configuration to that.